Xhosa language

| Xhosa | ||

|---|---|---|

| isiXhosa | ||

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Eastern Cape, Western Cape | |

| Total speakers | 7.9 million | |

| Ranking | 90 | |

| Language family | Niger-Congo

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | ||

| Regulated by | No official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | xh | |

| ISO 639-2 | xho | |

| ISO 639-3 | xho | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Xhosa (English pronunciation: /ˈkoʊsə/, Xhosa: isiXhosa [isikǁʰóːsa]) is one of the official languages of South Africa. Xhosa is spoken by approximately 7.9 million people, or about 18% of the South African population. Like most Bantu languages, Xhosa is a tonal language, that is, the same sequence of consonants and vowels can have different meanings when said with a rising or falling or high or low intonation. One of the most distinctive features of the language is the prominence of click consonants; The word "Xhosa", the name of the language itself, begins with a click.

Xhosa is written using a Latin alphabet-based system. Three letters are used to indicate the basic clicks: c for dental clicks, x for lateral clicks, and q for palatal clicks (for a more detailed explanation, see the table of consonant phonemes, below). Tones are not indicated in the written form.

Contents |

Affiliation and distribution

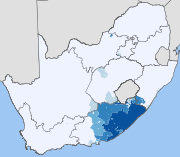

| 0–20% 20–40% 40–60% | 60–80% 80–100% No population |

| <1 /km² 1–3 /km² 3–10 /km² 10–30 /km² 30–100 /km² | 100–300 /km² 300–1000 /km² 1000–3000 /km² >3000 /km² |

Xhosa is the southernmost branch of the Nguni languages, which includes Swati, Northern Ndebele[1] and Zulu. There is some mutual intelligibility with the other Nguni languages, all of which share many linguistic features. Nguni languages are in turn part of the much larger group of Bantu languages, and as such Xhosa is related to languages spoken across much of Africa.[2]

Xhosa is the most widely distributed African language in South Africa, while the most widely spoken is Zulu.[2] Xhosa is the second most common home language in South Africa as a whole. As of 2003[update] the majority of Xhosa speakers, approximately 5.3 million, live in the Eastern Cape, followed by the Western Cape (approximately 2 million), Gauteng (671,045), the Free State (246,192), KwaZulu-Natal (219,826), North West (214,461), Mpumalanga (46,553), the Northern Cape (51,228), and Limpopo (14,225).[3] A minority of Xhosa speakers (18,000) exists in Quthing District, Lesotho.[4]

Dialects

Xhosa has several dialects, including

- Gcaleka

- Ndlambe

- Ngqika /Rharhabe (considered "standard")

- Thembu

- Bomvana

- Mpondomse (Mpondomise)

- Mpondo

- Xesibe

- Bhaca

- Cele

- Hlubi- There's still a debate about the whether the Hlubis belong to the Zulu, the Xhosa or they have their own King

- Mfengu[4]

There is some debate among scholars as to what exactly the divisions between the dialects are.

History

Xhosa-speaking peoples have inhabited coastal regions of southeastern Africa since before the sixteenth century. The members of the ethnic group that speaks Xhosa refer to themselves as the amaXhosa and call their language isiXhosa (isi- is a prefix relating to languages), while the language is most commonly known as "Xhosa" in English.

Almost all languages with clicks are Khoisan languages and the presence of clicks in Xhosa demonstrates the strong historical interaction with its Khoisan neighbours. An estimated 15% of the vocabulary is of Khoekhoe (Khoisan) origin.[4] In the modern period, Xhosa has also borrowed from both Afrikaans and English.

Role in modern society

The role of African languages in South Africa is complex and ambiguous. Their use in education has been governed by legislation, beginning with the Bantu Education Act of 1953.[2]

At present, Xhosa is used as the main language of instruction in many primary schools and some secondary schools, but is largely replaced by English after the early primary grades, even in schools mainly serving Xhosa-speaking communities. The language is also studied as a subject.

The language of instruction at universities in South Africa is English or Afrikaans, and Xhosa is taught as a subject, both for native and non-native speakers.

Literary works, including prose and poetry, are available in Xhosa, as are newspapers and magazines. The first Bible translation was in 1859, produced in part by Henry Hare Dugmore.[4] The South African Broadcasting Corporation broadcasts in Xhosa on both radio (on Umhlobo Wenene FM) and television, and films, plays and music are also produced in the language. The best-known performer of Xhosa songs outside South Africa is Miriam Makeba, whose Click Song #1 (Qongqothwane in Xhosa) and Click Song #2 (Baxabene Oxamu) are known for their large number of click sounds.

In 1996[update], the literacy rate for first-language Xhosa speakers was estimated at 50%, though this may have changed dramatically in the years since the abolition of apartheid.[4]

Linguistic features

Xhosa is an agglutinative language featuring an array of prefixes and suffixes that are attached to root words. As in other Bantu languages, Xhosa nouns are classified into fifteen morphological classes (or genders), with different prefixes for singular and plural. Various parts of speech that qualify a noun must agree with the noun according to its gender. These agreements usually reflect part of the original class that it is agreeing with. Constituent word order is Subject Verb Object.

Verbs are modified by affixes that mark subject, object, tense, aspect, and mood. The various parts of the sentence must agree in class and number.[2]

- Examples

- ukudlala - to play

- ukubona - to see

- umntwana - a child

- abantwana - children

- umntwana uyadlala - the child plays

- abantwana bayadlala - the children play

- indoda - a man

- amadoda - men

- indoda iyambona umntwana - the man sees the child

- amadoda ayababona abantwana - the men see the children

- Zonke zinto ezilungile zivela kuThixo - all things that are good proceed from God.

Vowels

Xhosa has an inventory of ten vowels: [a], [ɛ], [i], [ɔ] and [u], both long and short, written a, e, i, o and u.

Tones

Xhosa is a tonal language with two inherent, phonemic tones: low and high. Tones are frequently not marked in the written language, but when they are, they are a [à], á [á], â [áà], ä [àá]. Long vowels are phonemic but are usually not written, except for â and ä which are the results of gemination of two vowels with different tones each and have thereby become long vowels with contour tones (â high-low = falling, ä low-high = rising).

Consonants

Xhosa is rich in uncommon consonants. Besides pulmonic egressive sounds, as in English, it has 18 clicks (by way of comparison, the Juǀʼhoan language, spoken by roughly 10,000 people in Botswana and Namibia has 48 clicks, while the ǃXóõ language, with roughly 4,000 speakers in Botswana, has 83 click sounds, the largest consonant inventory of any known language), plus ejectives and an implosive. 15 of the clicks also occur in Zulu, but are used less frequently than in Xhosa.

The six dental clicks (represented by the letter "c") are made with the tongue on the back of the teeth, and are similar to the sound represented in English by "tut-tut" or "tsk-tsk" to reprimand someone. The second six are lateral (represented by the letter "x"), made by the tongue at the sides of the mouth, and are similar to the sound used to call horses. The remaining six are alveolar (represented by the letter "q"), made with the tip of the tongue at the roof of the mouth, and sound somewhat like a cork pulled from a bottle.

The following table lists the consonant phonemes of the language, giving the pronunciation in IPA on the left, and the orthography on the right:

| Labial | Dental / Alveolar |

Postalveolar / Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Lateral | ||||||

| Click | plain | [kǀ] c | [kǁ] x | [kǃ] q | |||

| aspirated | [kǀʰ] ch | [kǁʰ] xh | [kǃʰ] qh | ||||

| breathy voiced | [ɡǀʱ] gc | [ɡǁʱ] gx | [ɡǃʱ] gq | ||||

| nasal | [ŋǀ] nc | [ŋǁ] nx | [ŋǃ] nq | ||||

| breathy voiced nasal | [ŋǀʱ] ngc | [ŋǁʱ] ngx | [ŋǃʱ] ngq | ||||

| glottalized nasal[5] | [ŋ̊ǀˀ] | [ŋ̊ǁˀ] | [ŋ̊ǃˀ] | ||||

| Stop | ejective | [pʼ] p | [tʼ] t | [tʲʼ] ty | [kʼ] k | ||

| aspirated | [pʰ] ph | [tʰ] th | [tʲʰ] tyh | [kʰ] kh | |||

| breathy voiced | [bʱ] bh | [dʱ] d | [dʲʱ] dy | [ɡʱ] g | |||

| implosive | [ɓ] b | ||||||

| Affricate | ejective | [tsʼ] ts | [tʃʼ] tsh | [kxʼ] kr | |||

| aspirated | [tsʰ] ths | [tʃʰ] thsh | |||||

| breathy voiced | [dzʱ] dz3 | [dʒʱ] j | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | [f] f | [s] s | [ɬ] hl | [ʃ] sh | [x] rh | [h] h |

| breathy voiced | [v̤] v | [z̤] z | [ɮ̈] dl | [ʒ̈] zh2 | [ɣ̈] gr | [ɦ] hh | |

| Nasal | fully voiced | [m] m | [n] n | [nʲ] ny | [ŋ] n’ | ||

| breathy voiced | [m̤] mh | [n̤] nh | [n̤ʲ] nyh | [ŋ̈] ngh4 | |||

| Approximant | fully voiced | [l] l | [j] y | [w] w | |||

| breathy voiced | [l̤] lh | [j̈] yh | [w̤] wh | ||||

| Rhotic | fully voiced | [r] r1 | |||||

| breathy voiced | [r] r1 | ||||||

Two additional consonants, [r] and [r̤], are found in borrowings. Both are spelled r.

Two additional consonants, [ʒ] and [ʒ̈], are found in borrowings. Both are spelled zh.

Two additional consonants, [dz] and [dz̤], are found in loans. Both are spelled dz.

An additional consonant, [ŋ̈] is found in loans. It is spelled ngh.

In addition to the ejective affricate [tʃʼ], the spelling tsh may also be used for either of the aspirated affricates [tsʰ] and [tʃʰ].

The breathy voiced glottal fricative [ɦ] is sometimes spelled h.

The "breathy voiced" clicks, plosives, and affricates are actually plain voiced, but the following vowel is murmured. That is, da is pronounced [da̤].

Consonant changes with prenasalization

When consonants are prenasalized, their pronunciation and spelling may change. Murmur no longer shifts to the following vowel. Fricatives become affricates, and if voiceless, become ejectives as well, at least with some speakers: mf is pronounced [ɱp̪f’]; ndl is pronounced [ndɮ];n+hl becomes ntl [ntɬʼ]; n+z becomes ndz [ndz], etc. The orthographic b in mb is a voiced plosive, [mb].

When voiceless clicks c, x, q are prenasalized, a silent letter k is added – nkc, nkx, nkq – so as to prevent confusion with the nasal clicks nc, nx, nq.

Sample text

Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika is part of the national anthem of South Africa, national anthem of Tanzania and Zambia, and the former anthem of Zimbabwe and Namibia. It is a Xhosa hymn written by Enoch Sontonga in 1897. The first chorus is:

- Nkosi, sikelel' iAfrika;

- Malupakam'upondo lwayo;

- Yiva imithandazo yethu

- Usisikelele.

- Lord, bless Africa;

- May her horn rise high up;

- Hear Thou our prayers And bless us.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

- Bonke abantu bazalwa bekhululekile belingana ngesidima nangokweemfanelo. Bonke abantu banesiphiwo sesazela nesizathu sokwenza isenzo ongathanda ukuba senziwe kumzalwane wakho.

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of fellowship.

Qongqothwane ("The Knock-Knock Beetle," known in English as The Click Song) is a Xhosa wedding song best known as performed by Miriam Makeba. Note the frequent occurrence of palatal clicks:

- Igqira lendlela nguqongqothwane

- Igqira lendlela kuthwa nguqongqothwane

- Sebeqabele gqithapha bathi nguqongqothwane

- Sebeqabele gqithapha bathi nguqongqothwane.

- The diviner of the roadways is the knock-knock beetle

- The diviner of the roadways is said to be the knock-knock beetle

- It has passed up the steep hill, the knock-knock beetle

- It has passed up the steep hill, the knock-knock beetle

Common words and phrases

- Molo - hello (to one person)

- Molweni - hello (to more than one person)

- Unjani? - how are you? (one person)

- Ninjani? - how are you? (more than one person)

- Ndiphilile - I am well

- Siphilile - we are well

- Ngubani igama lakho? - What is your name?

- Unangaphi? - How old are you?

- Malini na? - How much money?

- Yintoni le? - What is this?

- Ngubani ixesha? (Nguban'ixesha) - What is the time?

- Kuyabanda ngaphandle! - It is cold outside!

- Enkosi - thank you

- Uxolo - excuse me

- Ngxesi - sorry

- Nceda - please

- Andiqondi/Andikuva - I don't understand

- Andiyazi - I don't know

- Ndithetha isiXhosa kancinci nje - I only speak a little Xhosa

- Ndiyagoduka ngoku - I am going home now

- Intwasahlobo ifikile - Spring has arrived

- Ndihamba ngebhasi - I go by bus

- Ndilahlekile - I am lost

- Ndingakwenzela ntoni? - What can I do for you?

- Vula iincwadi zakho - Open your books (to one person)

- Vulani iincwadi zenu - Open your books (to more than one person)

See also

- Xhosa calendar

- Henry Hare Dugmore, the first translator of the Scriptures into Xhosa

- U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, a 2005 Xhosa film adaptation of Bizet's Carmen

- UCLA Language Materials Project, an online project for teaching languages, including Xhosa.

References

- ↑ Online Xhosa-English Dictionary

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 UCLA Xhosa Language Materials Project

- ↑ South Africa Population grows to 44.8 Million.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Ethnologue report for language code:xho

- ↑ per Derek Nurse, The Bantu Languages, p 616. Zulu does not have this series.

External links

- Xhosa language profile (at UCLA Language Materials Project)

- Ethnologue report for Xhosa

- Xhosa-English Dictionary

- A very short Xhosa -> English dictionary

- Encouraging awareness of Xhosa culture and language

- PanAfrican L10n page on Xhosa

- Google in Xhosa

- Umholobo Wenene FM

- Xhosa learning resources

Software

- Spell checker for OpenOffice.org and Mozilla, OpenOffice.org, Mozilla Firefox web-browser, and Mozilla Thunderbird email program in Xhosa

- Translate.org.za Project to translate Free and Open Source Software into all the official languages of South Africa including Xhosa

|

||||||||||||||